Facsimile

Transcription

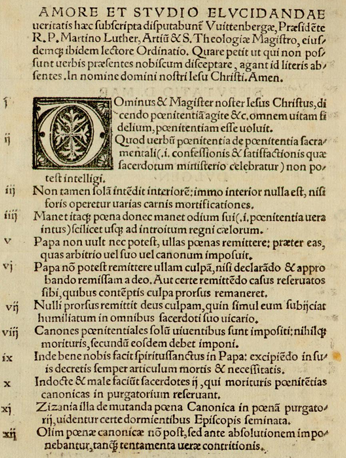

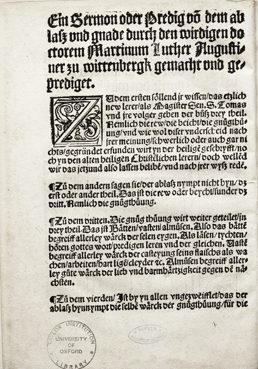

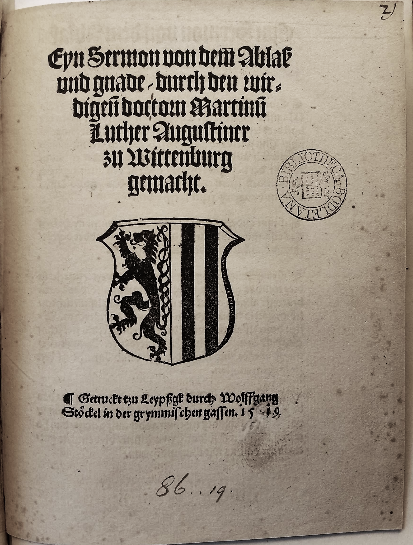

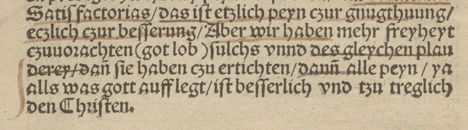

Eyn Sermon von dem Ablaß vnnd gnade durch den wirdigen̄ doctorn̄ Martinū Luther Augustiner zu Wittēbergk gemacht . 11 The Basel print has ‘ gemacht vnd geprediget ’ both here and on the title which immediately follows . Illustrations in the transcription from the Leipzig print which is edited here are marked ( L ) , from the Basel print ( B ) .

Eyn Sermon von dem Ablaß vnnd gnade / durch den̄ wirdigen̄ doctorn̄ Martinum Luther Augustiner zu Wittenbergk geprediget .

¶ Czum Ersten solt yr wissen / das eczlich 22 The spelling ‹ cz › represents [ ts ] ( see ‘ How to Read the Sermon ’ , 5 ) ; the word is the reflex of MHG eteslich with syncope ; the form ‘ etlich ’ ( 9 ) is the reflex ( also with syncope ) of the variant MHG form etelich . Over time , ‹ cz › is replaced by ‹ z › in Luther’s writings . new lerer / als 33 = NHG wie ; see §19 ( paragraph references are to ‘ Language and Style ’ in the Introduction ) . Magister Sentē . S. Thomas vn̄ yhre folger gebē d ’ pusz 44 Initial ‹ p › instead of ‹ b › here and in ‘ peycht ’ later in the sentence reflects a pronunciation associated particularly with Bavarian , which influenced the spelling of East Central German texts at this time . drey 55 The spellings ‹ ey › and ‹ ei › can be taken as interchangeable ; over time ‹ ei › comes to prevail in Luther’s writings . teyl / Nemlich die rew / die peycht / die gnugthuung 66 On ‹ gn › , see §1 ; on ‹ th › , see §4 . / Vn̄ wiewol diszer vnderscheyd 77 MHG had the forms underscheit ( of which this is the reflex ) and underschiet ( of which NHG Unterschied is the reflex ) . nach yrer meynung / schwerlich adder 88 = NHG oder ; this word also appears with ‹ o › , e.g. in 9 ; the spelling with ‹ dd › here is consistent with a preceding vowel probably pronounced short at this time ( see §§3 and 12 ) . auch gar nichts 99 = NHG nicht ; nicht and nichts were to some extent interchangeable in ENHG . / gegrundet erfunden 1010 = MHG gefunden ; but see 9 , where it means NHG erfunden . wirt in der heyligenn schrifft / noch 1111 noch ‘ nor ’ can occur even without a preceding weder in ENHG . in den alten heyligen Christlichen lerern̄ / doch wollē wir das ycztszo 1212 = NHG jetzt so ; on the lack of spacing , see ‘ How to Read the Sermon , 7 ’ ; on initial ‹ y › , see §14 . lassen bleyben / vnd nach yrher weysz reden .

¶ Czum andernn̄ 1313 ander co-existed with zweit - in ENHG as the word for ‘ second ’ . sagen 1414 ‘ sagten ’ in B. sie / der ablasz 1515 The clause starting ‘ der ablasz ’ is an unintroduced subordinate clause ; see §20 . nympt 1616 On ‹ p › , see §6 . nycht hynn das erst adder ander teyll / das ist / die rew adder peycht / sunderū 1717 The print clearly has ‹ ū › , which must be a mistake for ‹ n › . das dritt / nemlich die gnugthuung .

¶ Czum Driten . die gnugthuung wirt weyter geteylet in drey teil 1818 On the placement of such elements outside the verbal bracket , see §22 . / das ist / Beeten 1919 On ‹ ee › , see §2 . / vastē / almuszē / also / das beetē begreyfft allerlei werck der seelē 2020 On the weak ending , see §16 . eygē / als leszē / tichten 2121 = NHG dichten ; the spelling with ‹ d › ( adopted in NHG ) reflects the derivation of this word from Latin dictare . / horen 2222 On the non-marking of umlaut in this print , see §8 . gottes wort / predigen / leeren vnd d’gleichen . Uasten begreiff allerlei werck der casteyūg seins fleyschs / als 2323 = NHG wie . wachen / erbeiten 2424 = NHG arbeiten , with umlaut of [ a ] > [ e ] conditioned by the following [ ei ] ; this is a characteristically East Central German form ; cf. ‘ arbeiten ’ in B. / hart 2525 For the lack of inflectional ending , see §16 . lager 2626 ‘ ligē ’ ‘ lying ’ in B. / cleider &c. Almuszē begreyff allerlei gute werck 2727 For the lack of inflectional ending , see §16 . der lyeb vn̄ barmherczickeyt gegen dem nehsten . 2828 Note dative after gegen as opposed to accusative in NHG .

¶ Czum Uierden 2929 In this ordinal number , as well as in sibende and others ending - nde , ‹ d › > ‹ t › between ENHG and NHG by analogy with ordinal numbers such as erste - , dritte - , fünfte - . The ‹ d › in ‘ Uierden ’ dates back to Old High German ( fiordo ) , and in those ending - nde to MHG . / Jst bey yhn allē vngeczweyfelt 3030 ‘ vngeczweyflet ’ in B ; the ending would originally have been - elet , and the two prints reflect syncope of different unstressed vowels ( see §1 ) . / das der ablas hin nympt die selben werck der gnugthuūg / vor 3131 = NHG für ; see §19 . die sund schuldig czuthun 3232 ‘ schuldig czuthun ’ qualifies ‘ sund ’ and means ‘ due ( to be done ) ’ ; this sense of schuldig is not found in NHG . adder auffgeseczt / dannn 3333 On ‹ nnn › , see §3 . szo 3434 ‘ if ’ ; see §19 . er die selben werck solt all hin nehmen / blieb nichts gutes mehr da / das wir thun mochtenn . 3535 Here = NHG könnten .

a2r ¶ Czum Funfften . Jst bey vielē gewest 3636 This form of the past participle as well as gewesen occurred across the High German dialect areas at this time . eyn große vn̄ noch vnbeschloszene opiny 3737 This loan word from Latin opinio is rarely attested in ENHG . / Ab 3838 = ob ; see §§12 and 19. der ablas auch etwas mehr hynnehme / dann̄ 3939 = NHG als ; see §19 . solche auffgelegte gute werck / nemlich / ab er auch die peyne / die die gotlich gerechtigkeyt / vor die sunde / fordert / abnehme .

¶ Czum Sechsten . Lasz ich yhre opiny vnuorworffen̄ auff das 4040 ‘ disz ’ in B. mal / Das sag ich / das mā ausz keyner schrifft bewerenn kan̄ / das gottlich gerechtigkeyt etwas peyn adder gnugthuung begere adder fordere 4141 On the use of the subjunctive , see §20 . / vonn dem sunder . Dan̄ 4242 Here = ‘ except ’ . allein seyne herczliche vnd ware rew adder bekerūg myt vorsacz hynfurder 4343 = NHG fürderhin . / das Creucz Christi 4444 A Latin genitive singular ending ; see §18 . czu tragenn / vnnd die obgenanten werck ( auch von nyemāt auffgeseczt ) czu vben / Dan̄ szo 4545 ‘ also ’ in B. spricht er durch Ezechie . Man 4646 Comparison with ‘ M’aria ‘ M’agda . later in this point shows that there is indeed an ‘ M ’ in ‘ Man ’ . The spelling may be deliberate , as wan ( here = NHG wenn ) is sometimes spelt man in ENHG ; alternatively it could be a mistake , or the printer might have run out of the rare letter ‘ W ’ ( the only genuine ‘ W ’ in the text occurs in ‘ Wittenbergk ’ in the title ) . B has ‘ wan ’ . sich der sunder bekeret / vn̄ thut recht / so will ich seyner sunde nicht mehr gedencken . Jtem also hatt er selbs 4747 On the absence of final ‹ t › , see §5 . all die absoluirt . 4848 Note that Luther uses a loan word here ( from Latin absolvēre ) for a technical theological term for which there was no native equivalent . Maria Magda . 4949 = ‘ Magdalena ’ . den gichtpruchtigē . 5050 = NHG gichtbrüchig . Die eebrecherynne &c. Un̄d mocht 5151 The personal pronoun ‘ ich ’ is omitted before ‘ mocht ’ ( = NHG ich möchte ) ; this sometimes occurs in ENHG when the pronoun is obvious in context . woll 5252 On the meaning of ‘ wol ’ , see §19 . gerne horen wer das anders bewerē soll . Unangesehen das eczlich doctores 5353 A Latin nominative plural ending ; see §18 . szo gedaucht 5454 On this form , see §17 . haben .

¶ Czum Sibenden . Das findet man woll / das gott eczlich nach seyner gerechtigkeyt straffet / Ader durch peyne dringt czu der rew / wie ym .88 . p̄s . 5555 Abbreviation for ‘ Psalm ’ ( abbreviated to ‘ Psal. ’ in B ) . Szo seyn kinder werden sundigen 5656 ‘ sünden ’ in B. / will ich myt der ruthen 5757 For this weak ending , see §16 . / yhre sunde heym suchen / Aber doch meyn barmherczickeyt nit 5858 This form represents nicht with weak speech stress ; both forms are found in this text ; in Luther’s later writings nicht predominates . vonn yhnn 5959 = NHG ihnen . wendē . Aber disze peyne / stehet in nyemandes gewalt nachczulassen / dann̄ alleyne gottis . 6060 The spelling ‹ i › for the unstressed vowel [ ə ] is associated particularly with the Central German dialect area in ENHG . Ja er will sie nit lassen / sūder vorspricht 6161 On vor - rather than ver - , see §13 . / er woll sie aufflegē . 6262 ‘ er woll sie aufflegē ’ is an unintroduced subordinate clause ; see §20 .

¶ Czum Achten . Der halbē 6363 = NHG deshalb ; this and the following ‘ szo ’ are both adverbs meaning ‘ for this reason ’ . szo kann man der selbē gedunckten peyn / keynen namen geben / weysz 6464 According to NHG grammar we should expect an expletive ‘ es ’ before ‘ weysz ’ to ensure that the finite verb is the second constituent in the clause . auch nyemant / was sye ist / szo 6565 The word order which follows , with the finite verb in final position , tells us that this is a subordinate clause ( with ‘ szo ’ meaning ‘ if ’ here ) . sie disze straff nyt ist . auch dye guten / obgenanten werck nit ist .

a2v ¶ Czum Neunden . Sag ich / ob 6666 = NHG auch wenn ‘ even if ’ ; see §19 . die Christenliche kirch noch heut beschlusz / vnd ausz ercleret / das 6767 In NHG syntax , ‘ das ’ ( = dass ) would immediately follow ‘ Sag ich ’ at the beginning of the sentence ; in ENHG the delayed position , which avoids the nesting of one subordinate clause in another , is not uncommon . der ablas mehr dan̄ die werck der gnugthuūng hyn neme 6868 ‘ beschlusz ’ , ‘ ausz ercleret ’ , and ‘ hyn neme ’ are preterite subjunctives ( their NHG equivalents are beschlösse , auserklärte , and hinnähme ) , as are ‘ loszet ’ , ‘ begeret ’ , ‘ thetten ’ , and ‘ litten ’ later in the sentence . / szo were es den nocht 6969 On final ‹ t › , see §5 . tausentmal besser / das keyn Christen mensch den ablas loszet oder begeret / sundern̄ das sye lieber die werck thetten vnnd die peyn litten / dan̄ der ablas / nit anderst ist nach 7070 = noch ; see §12 . mag werden / dan̄ nachlassung gutter werck / vnnd heylsamer peyn / die man billich solt erwellē dann̄ vorlassen / wiewol etlich d er newen prediger zweyerley peyne erfunden 7171 Preterite plural of erfinden ( NHG erfanden ) . / Medicatiuas Satisfactorias 7272 Latin accusative feminine plural endings ; see §18 . / das ist etzlich peyn czur der gnugthuūng / eczlich czur der 7373 Note the pleonastic ‘ czur ’ ( = zu der ) + ‘ der ’ . besserung / Aber wir haben mehr freyheyt czuuorachten 7474 Note that ‘ czuuorachten ’ ( NHG zu verachten ) would occur after the object ‘ plauderey ’ in NHG . ( got lob ) 7575 ‘ got zů lob ’ in B. sulchs 7676 The spelling with ‹ u › is characteristic of East Central German ( cf. ‘ solichs ’ in B ) ; ‘ sulchs ’ and ‘ des ’ are genitive singulars with the substantival adjective ‘ gleychen ’ ; cf. English suchlike . vnnd des gleychen plauderey / dan̄ sie haben czu ertichten / dann̄ alle peyn / ya 7777 A modal particle ; see §27 . alls was got auff legt / ist besserlich vnd tzu treglich 7878 ‘ zůtraͤglicher ’ in B. den Christen .

¶ Czū czehenden / Das ist nichts 7979 Here = NHG nicht . geredt / das der peyn vnnd werck czu vill 8080 ‘ der peyn vnnd werck ’ are partitive genitives dependent on ‘ czu vill ’ ; see §21 . seynn 8181 This could represent NHG sind ( indicative ) or NHG seien ( subjunctive ) ; see §§17 and 20. / das der mensch sye nit mag vol brengen 8282 Vowel lowering ( here of [ i ] to [ ɛ ] ) is characteristic of Central German ; cf. ‘ volbringen ’ in B. This and the lowering of [ u ] > [ o ] and of [ ü ] > [ ö ] were conditioned particularly by a following nasal or l / r + consonant ; see notes to ‘ sunst ’ in 13 and ‘ furdert ’ in 14. / der kurcz halben 8383 = NHG halber . seyns lebens / Darumb 8484 Given the delayed position of the verb in this clause , we can take ‘ Darumb ’ as an adverbial relative ( ‘ for which reason ’ ; = NHG worum ) rather than as a demonstrative ( ‘ for that reason ’ ) . yhm nott sey der Ablas . Antwort ich das / das kein grundt 8585 On ‹ dt › , see §4 . hab / vn̄ eyn lauter geticht 8686 In ENHG this could refer generally to something made up , not just a poem as in NHG Gedicht . ist / Dan̄ gott vnnd die heylige kirche / legen nyemand mehr auff / dan̄ yhm 8787 B has the plural ‘ yn ’ here rather than the singular . czu tragē muglich 8888 Forms of this word with ‹ u › or , reflecting lowering before a nasal , with ‹ o › co-existed in a number of dialect areas ; similarly ‘ kunen ’ a few lines below . ist / als auch . S. Paul sagt / das got nit leszt vorsucht werden yemand / mehr dan̄ er mag tragen / vnd es langet 8989 NHG langen no longer has this sense ; a semantic equivalent is gereichen . nit wenig czu der Christenheyt schmach 9090 On the order of noun and dependent genitive , see §21 . / Das mā yhr schuld gibt / sye lege auff mehr / dan̄ wir tragen kunen . 9191 ‘ sye ... kunen ’ is an unintroduced subordinate clause ; see §20 . B has ‘ moͤgen ’ rather than ‘ kunen ’ .

¶ Czum eylfften . 9292 = NHG elften ; cf. MHG einlif ‘ eleven ’ . Wann gleych 9393 = NHG wenngleich . die pusz ym geystlichē recht geseczt / iczt 9494 = NHG jetzt ; see §14 . noch ginge 9595 On the use of the subjunctive ; see §20 . B has the plural ‘ gingen ’ here ; ‘ die pusz ’ could be singular or plural ( see §16 ) . / Das vor ein yglich todtsund / syeben iar pusz auffgelegt were / Szo must doch die Christenheyt / dye selbē gesecz lassen / vn̄ nit weyter aufflegen / dan̄ sye eynem yglichen 9696 ‘ jetlichen ’ in B. czu tragē warē . 9797 = NHG wären . Uil weniger / nu 9898 = ‘ now that ’ ; B has ‘ so ... nun ’ . sye iczt nicht seyn / sall 9999 On the spelling with ‹ a › , see §12 . mā achtē 100100 B has ‘ so soll man achtē / das meer ’ instead of ‘ sall mā achtē / das nicht mehr ’ . / das nicht mehr auffgelegt werde 101101 On the use of the subjunctive , see §20 . dan̄ yederman wol tragē kan .

a3r ¶ Czum czwelfftē . 102102 On the spelling with ‹ e › , see §11 . Man sagt wol / das der sunder mit der vberingen 103103 = NHG übrigen ; the insertion of ‹ n › may reflect colloquial pronunciation . peyn inszfegfewr 104104 = ‘ insz fegfewr ’ ; on the lack of spacing , see ‘ How to Read the Sermon , 7 ’ . oder czum ablas geweyset sall werdenn / aber es wirt wol mehr dings 105105 A partitive genitive ( see §21 ) ; lit . ‘ more of thing ’ . / an 106106 In ENHG an ( e ) , ‹ a › = [ a : ] ; this was later raised and rounded to [ o : ] in NHG ohne . grundt vnd bewerung gesagt .

¶ Czum Dreyczehendē . Es ist eyn groszer yrthū das yemādt meyne / er wolle gnugthun vor seyne sundt / so doch got die selbē alczeyt vmb sunst 107107 = NHG umsonst ; on ‹ b › , see §6 ; for the later lowering of [ u ] to [ o ] , see note to brengen in 10 above . / ausz vnscheczlicher gnad vorczeyhet / nichts darfur begerend / dā hynfurder woll leben . 108108 NHG would have zu leben . Die Christenheyt fordert wol etwas / also mag sie vnd sall auch das selb nachlassen / vnnd nichts schweres adder vntreglichs auflegen .

¶ Czum Uierczehendē . Ablasz wirt czu gelassen vmb der vnuolkōmen vnd faulen [Christen] 109109 ‘ Christeu ’ seems to be a clear error for ‘ Christen ’ . willen / die sich nit wollen kecklich 110110 ‘ lively ’ ; etymologically related to Engl quick . vben in guten wercken / oder vnleydlich seyn / dan̄ ablas furdert 111111 = fürdert ; for the later lowering of [ ü ] to [ ö ] as in NHG fördert , see note to brengen in 10 above . nyeman czum bessern / sundern duldet vnnd zuleszet yr vnuolkōmen 112112 = NHG Unvollkommenheit ( as it appears in B ) . / darumb soll man nit wider das 113113 The noun was masculine or rarely , as here , neuter , in ENHG . ablas redenn / man sall aber auch nyemand darczu 114114 = NHG dazu ; the construction is not found in NHG and is equivalent to niemandem dazu raten or niemandem in dieser Sache zureden . reden .

¶ Czum Funffczehenden . Uill sicherer / vnnd besserer 115115 Note the redundant - er . thet der / der lauter vmb gottes willen / gebe czu dē gebewde . S. Petri 116116 Abbreviation for ‘ Sancti Petri ’ , a Latin genitive singular ; see §18 ; cf. ‘ sanct Peters ’ with a German genitive ending in 16. / ader was sunst genāt wirt / Dan das er ablasz darfur nehme 117117 ‘ thet… gebe… nehme ’ are preterite subjunctives ( = NHG täte… gäbe… nähme ) . / dann̄ 118118 Note that the causal conjunction ‘ dann̄ ’ is followed by subordinate-clause word order here . es ferlich 119119 ≈ NHG gefährlich . ist / das er sulch gabe vmb desz ablas 120120 For lack of genitive singular ending , see §1 . willē vn̄ nit vmb gotts willē gibt

¶ Czum Secheczehendē . 121121 The ‹ e › in the middle of ‘ Sech e czehendē ’ is unhistoric and does not appear in B or in the Wittenberg prints . Uill besser ist das werck eynen 122122 We should expect the dative ‘ einem ’ here ; the nasal bar in B ( ‘ einē ’ ) could stand for ‹ n › or ‹ m › , and ‹ n › here may be an error . durfftigen erczeygt / dan das czum gebewde geben 123123 = ‘ gegeben ’ . wirt auch vill besser / dan der ablas dafur gegebē / dan wie gesagt . Es ist besser eyn gutes werck gethā / dann̄ vill nach gelassen . Ablas aber / ist nachlassung villgutter werck / ader ist nichts nach gelassen . a3v Ja 124124 B has ‘ Aber ’ here . das ich euch recht vnderweise . szo merckt auff / du salt 125125 = NHG sollst and later ‘ wilt ’ = NHG willst ; [ s ] was added by analogy with verbs whose second person singular ended - st ( already in ‘ magstu ’ below ) . Note the switch from second-person plural to second-person singular between ‘ merckt ’ and ‘ salt ’ . vor allenn dingen ( widder 126126 = NHG weder , often spelt with an ‹ i › in Luther’s early writings ; the spelling with ‹ dd › here is consistent with a preceding vowel probably pronounced short in both weder and wider at this time ( see §3 ) . sanct Peters gebewde noch ablas angesehen ) deynē nehsten armē geben / wiltu 127127 On contracted forms , see §7 . etwas geben . Wan̄ esz aber dahyn kumpt 128128 On ‹ p › , see §6 . / das nyemandt yn deyner stat mehr ist der hulff 129129 ENHG texts show widespread variation : helfe , hilfe , hülfe ( B : ‘ hilff ’ ) . bedarff ( das ob gotwill nymer gescheen 130130 The omission of ‹ h › here suggests that it was no longer pronounced in medial position , which is consistent with its use as a length marker ; see §2 . sall ) dan̄ saltu geben szo du wilt tzu den kirchen / altarn / schmuck / kelich 131131 = NHG Kelch ; an early loan word from Latin calix with umlaut of [ a ] > [ e ] . / die in deyner stat seyn . Und wen das auch nu nit mehr not ist / Dan̄ aller erst / szo du wilt / magstu geben zu dē gebewde . S. Peters adder anderwo . Auch soltu dannochnit das vmb ablas willen thun . dann̄ 132132 Note the redundant abbreviation ; see ‘ How to Read the Sermon , 2 ’ . sant Paul spricht Wer seynē hausz genoszē nit wol thut / ist keyn Christē vnd erger dan̄ ein heyde / vn̄ halts 133133 = ‘ halt es ’ . dafur frey / wer dir āders sagt / der vorfurt dich / adder sucht yhe 134134 The function of ‹ h › here may be to indicate that the following , rather than the preceding , vowel is long ( cf. §2 ) . dein seel in deynem Beutell vnd fund 135135 For this form , see §17 . er pfenning darinne / das were 136136 According to NHG word order , ‘ were ’ ( = NHG wäre ) would occur first in this clause ; in ENHG it was usual not to invert subject and verb when a main clause followed a subordinate clause . ym lieber dan̄ all seelē . Szo sprichttu . 137137 Note that ‹ s › is missing here ; cf. ‘ sprichst du ’ in B. Szo werd ich nymer mehr ablas loszen . Antwort ich / das hab ich schon obē gesagt / Das meyn will / begirde / bitt vn̄ ratt ist / das nyemandt ablas losze / lasz die faulen vnd schlefferigen Christen / ablas loszen / gang 138138 A widespread form of the imperative singular of gehen in ENHG . du fur dich .

¶ Czum Sibenczehenden . Der ablas ist nich 139139 On lack of final ‹ t › , see §5 . geboten auch nicht geratē / sundern̄ von der dinger czall 140140 On the order of noun and dependent genitive , see §21 . / die czu gelassen vn̄ erleubt 141141 The umlauted form of this verb is associated particularly with East Central German ( cf. ‘ erloubt ’ in B , and see ‘ geleub ’ for NHG glaube in 18 ) . werdē . darumb ist es nit eyn werck des gehorsams / auch nit vordinstlich 142142 = NHG verdienstvoll . / sundern̄ eyn ausz czug des gehorsams . Darumb wiewol man / nyemant weren 143143 = NHG verwehren . soll / den czu loszen / szo solt mā doch alle Christē daruon cziehen / and zu den wercken vn̄ peynen / die do nachgelassen 144144 ‘ seyn / sind ’ must be understood after ‘ nachgelassen ’ ; auxiliary verbs were sometimes omitted in ENHG subordinate clauses . reyczen vnd sterckenn̄ .

¶ Czum Achtczehendē . Ab die seelen ausz dē fegfewr geczogen werden durch den ablas / weysz ich nit / vn̄geleub das auch noch nich / wiewol das eczlich new doctores sagen / aber ist yhn vnmuglich czubeweren / auch hat es die kirch noch nit beschlossen / darumb czu meh a4r rer 145145 Note that mehr could serve as an adjective in ENHG . sicherheyt / vil besser ist es 146146 The clause ‘ darumb … es ’ is either a main clause in which the finite verb ‘ ist ’ is delayed or a subordinate clause in which the finite verb and pronominal subject are ( unusually ) inverted at the end . / das du vor sie selbst bittest vn̄ wirckest / dann disz ist bewerter vn̄ ist gewisz

¶ Czum Neunczehendē . Jn dissen puncten hab ich nit czweyffel / vnnd sind 147147 Note that the subject sie would have to be specified before ‘ sind ’ in NHG . gnugsam inder schrifft gegrund . 148148 On the omission of the ending - et , see §1 . Darumb solt ir auch keyn czweyffel haben / vn̄ last doctores Scholasticos / scholasticos 149149 Latin accusative plural endings ; see §18 . sein / sie sein alsampt 150150 On ‹ p › , see §6 . nit gnug / mit yhren opinien / das sie eyne prediget befestigenn soltenn .

¶ Czum czwenczigsten . 151151 Forms of this word with ‹ e › and ‹ a › alternate in ENHG . Ab etzlich mich nu wol 152152 Morphologically , ‘ Ab ’ and ‘ wol ’ should be taken together as a single conjunction like NHG obwohl ; however , the conjunction means ‘ even if ’ rather than ‘ although ’ here . eynen keczer 153153 ‘ eynen keczer ’ is in apposition to ‘ mich ’ : ‘ as a heretic . ’ schelten / den 154154 = NHG denen . solch warheyt seer schedlich ist im kasten . Szo acht ich doch solch geplerre nit grosz / sintemal 155155 ‘ since ’ ; < MHG sint dem mâle ‘ since that time ’ . das nit thun / dan̄ eczlich finster gehyrne / die die Biblien 156156 On the weak ending , see §16 . nie gerochē / die Christenlichē lerer nie geleszē 157157 The lack of punctuation is explained by the fact that ‘ geleszē ’ is followed by a line break in the print ; see ‘ How to Read the Sermon , 1 ’ . yhr eigen lerer 158158 B has ‘ lere ... leren ’ ( NHG Lehre ( n ) ) as opposed to ‘ lerer ... lerer ’ ( NHG Lehrer ) here . nie vorstanden 159159 The auxiliary verb ‘ haben ’ must be understood here . / sundern in yhren lochereten 160160 = NHG löcherig ; löcheret derives from MHG löchericht with weakening of - icht to - et . vnd czurissen 161161 = NHG zerrissenen ; the NHG prefix zer - appears as czu / zu - or czur / zur - throughtout Luther’s writings ; on the loss of - en , see §1 . opinien vill nah vorwesen / dā hetthen sie die vorstanden szo wisten 162162 On this form , see §11 . sie / das sie nyemādt solten lestern / vnuorhort vn̄ vnuberwundē / doch got geb yhn / vnd vns rechten sinn . Amen .

Forms of this word are commonly found with initial ‹ t › and ‹ d › in ENHG .

Nach Christ geburt Tausent funff hundert vn̄ ym 164164Note that ‘ ym ’ occurs immediately before the inflected form , thus breaking up the numeral .

achczehenden Jar.Translation

About

About this text

Identification

Oxford, Taylor Institution Library, ARCH.8o.G.1518 (6)L 6270About this edition

This is a facsimile and transcription of Eyn Sermon von dem Ablass vnnd Gnade. Luther, Martin, and Valentin Schumann | Leipzig: [Valentin Schumann], 1518. It is held by the Taylor Institution Library (shelf mark: ARCH.8o.G.1518(6)). Verzeichnis der im deutschen Sprachbereich erschienenen Drucke des 16. Jahrhunderts (VD 16) reference number: L6270.

The transcription was created by Christiane Rehagen, and encoded in TEI P5 xml by librarian Emma Huber.

The footnotes were created by Howard Jones. Some references are to the printed book.

Introduction

The Sermon von Ablass und Gnade ( Sermon on Indulgences and Grace ) is a seminal text for the Reformation : it is the first vernacular statement of Luther’s views on the question which led to his break with Rome ; the first printed work of his to reach a mass audience ; and the first example of the direct , arresting style which became the hallmark of his German writings . The work hit the market 500 years ago , in the second half of March 1518 , five months after the posting of the 95 Theses , and within three years at least 24 editions had been printed in various parts of Germany and Switzerland . Our volume is based on two of these editions , copies of which are held in the Taylor Institution Library , and presents a guide to the theological , historical , material , linguistic , and stylistic importance of this work .

The Sermon rejects scholastic teaching about indulgences and proposes instead a theology of grace . Luther meant the Sermon as an accessible summary of his views , and for the modern reader it is still the most succinct account of Luther’s side in the indulgence controversy , serving as an introduction to the more technical 95 Theses which are also included in Latin and English in this edition . The theological and historical context of the Sermon and 95 Theses is complex and dates back centuries before the actual texts . We explain this background and provide an evaluation of both works in ‘ Theological and Historical Background ’ .

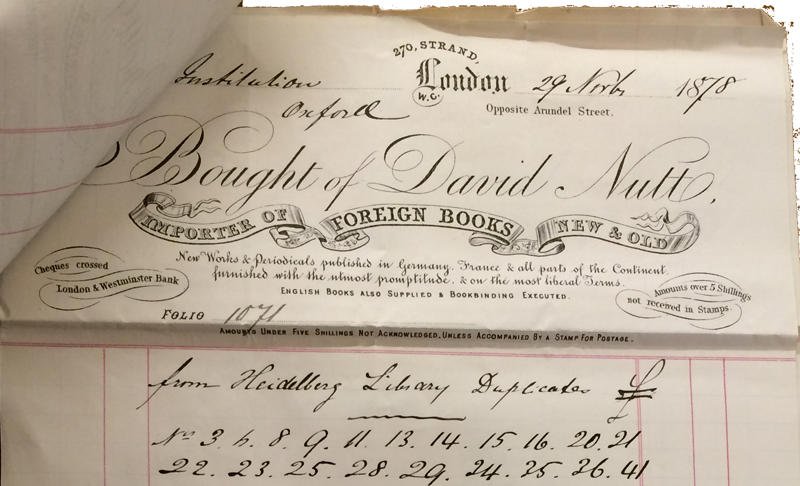

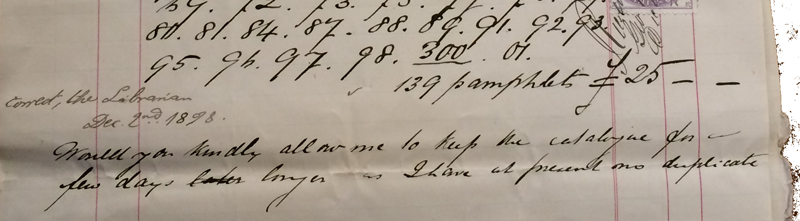

This volume includes side-by-side facsimiles of the two Taylorian copies on facing pages along with an edition based on the Leipzig edition and a new translation into modern English . We offer a detailed guide to the book-history in ‘ The Taylorian Copies ’ ( including an analysis of the woodcuts in the Basel edition and the marginalia added to the Taylorian copy of the Leipzig edition ) , a preview to the follow-up pamphlets in the debate ( cf. ill . 2 ) , and an account of the acquisition history .

Ill. 2 : Luther’s follow-up pamphlet in the Taylorian Collection Eyn Freyheyt Deß Sermons Bebstlichē ablaß vnd gnad belangend , Taylor Institution Library , Arch. 8° G. 1523 ( 43 / 2 ) [ Leipzig : Valentin Schumann 1518 ] , VD16 L 4741

By putting his arguments in the vernacular , Luther could simultaneously address experts and win over the general public , whereas only the former was possible in Latin . This first publishing success was followed by a stream of sermons , treatises , and other pastoral , polemical , and political writings over the next few years , all written in an evolving but distinctive style of German . In ‘ Language and Style ’ , we offer a linguistic analysis of the Sermon , highlighting differences from modern German , dialect features of these two editions ( East Central German and Low Alemannic ) , and some of the stylistic qualities which were to characterize Luther’s German writing for the rest of his career .

This is the first time that these two editions have been made available to a modern audience . To make the Early New High German text in its original spelling accessible for students of Linguistics as well as Theology and History , a guide on ‘ How to Read the Sermon ’ is included . Of the two Taylorian copies , the one published in Leipzig by Valentin Schumann is probably more similar to what Luther wrote than the Basel one by Pamphilus Gengenbach , since the text is closer to the earliest Wittenberg version of the Sermon . We therefore use the Leipzig edition as the basis for the facing transcription to the new translation . At editions . mml.ox.ac.uk the Basel edition has also been transcribed as a further example of printed material and of the variation that could exist between different versions of the same work – in appearance , dialect , and content .

Emma Huber , Howard Jones , Martin Keßler , Henrike Lähnemann , and Christina Ostermann Oxford , March 2018

Anno Domini 1518. End of the Leipzig print of the Sermon Taylor Institution Library , Arch. 8° G. 1518 ( 6 ) ,

1. Theological and Historical Background

Luther’s 95 Theses are widely considered to mark the beginning of the Reformation . Over the course of four centuries , beginning in Saxony in 1617 , 31 October has established itself as the pivotal date in Reformation memory . 1.1. Thomas Kaufmann , Das Reformationsjubiläum 1617 , in : Thomas Kaufmann , Dreißigjähriger Krieg und Westfälischer Friede . Kirchengeschichtliche Studien zur lutherischen Konfessionskultur , Tübingen 1998 ( Beiträge zur historischen Theologie 104 ) , 10 – 23. While the epoch-making , heroic image of Luther nailing his series of disputation theses to the doors of Wittenberg’s Castle Church has been questioned and debated for six decades , it is clear that such as an act would have been anything but spectacular . 2.2. The best summary of the earlier discussions is in a series of articles in : Geschichte in Wissenschaft und Unterricht . Zeitschrift des Verbandes der Geschichtslehrer Deutschlands 16 / 11 ( 1965 ) , 661 – 99. For more recent considerations see Joachim Ott and Martin Treu ( eds ) , Luthers Thesenanschlag – Faktum oder Fiktion , Leipzig 2008 ( Schriften der Stiftung Luthergedenkstätten in Sachsen-Anhalt 9 ) and Uwe Wolff ( ed. ) , Iserloh . Der Thesenanschlag fand nicht statt , Basel 2013 ( Studia oecumenica Friburgensia 61 ) . Disputation theses were addressed to the academic public , accordingly written in Latin , displayed on the local church doors which served as the university’s notice board , and sometimes also sent to other scholars . If this is what Luther did , he did not stop there , for he also sent his theses to senior representatives of the local church hierarchy . On 31 October 1517 , the eve of All Saints ’ Day , he attached his theses to a letter to Archbishop Albrecht of Mainz and Magdeburg . 3.3. Luther’s writings ( WA ) und letters ( WA . Br ) are quoted from D. Martin Luthers Werke . Kritische Gesamtausgabe , 120 vols , Weimar 1883 – 2009 ; here : WA . Br 1 , 110 – 12. Parts of the letter are translated by Hans J. Hillerbrand ( ed. ) , The Protestant Reformation . Revised edition , New York [ etc. ] 2009 , 25 – 27. In his own account from 1518 and in later years , Luther mentions also having written to Hieronymus Scultetus , Bishop of Brandenburg and Havelberg . 4.4. Cf. WA . Br 1 , 113 – 14 , and for further important references Hans Volz , Martin Luthers Thesenanschlag und dessen Vorgeschichte , Weimar 1959 , 19 – 23. If these recollections are accurate , Luther was engaging with two senior echelons of the church right from the start . As it turned out , these formal steps , together with the theological content of what he wrote and the legal claims he made about the sale in indulgences at the time , triggered a chain of events that led within three years to Luther’s excommunication .

What made the 95 Theses special and how can one best study this classic piece of Reformation history ? The present edition provides various answers and offers one practical suggestion : ease yourself in gently by reading the Sermon on Indulgences and Grace and then proceed to the theses . Why ? Because – to put it bluntly – the 95 Theses would otherwise be largely incomprehensible . Even scholarly readers accept that the theses taken on their own demand explanation and exposition , but this simply illustrates the nature of disputation theses . 5.5. Cf. Anselm Schubert , Libertas Disputandi . Luther und die Leipziger Disputation als akademisches Streitgespräch , in : Zeitschrift für Theologie und Kirche 105 ( 2008 ) , 411 – 42. They were intended for an academic debate in which authorities and arguments were tossed back and forth . In academic disputations the pros and cons were represented by two sides – individuals or groups – , those of opponent and respondent . The opponent’s task was to cite counter-arguments to the theses – whether from biblical authority , patristic sources , theological doctrine , legal tradition , or general reason and experience – , while the respondent had to evaluate and develop the arguments . Luther’s 95 Theses fit into this pattern : they provide the basis for a more detailed and structured exchange , and they are neither sufficient nor self-explanatory . They invite contradiction or agreement on the basis of solid authority . The author’s own comments , clarifications , or conclusions were sometimes documented in subsequent explanations . When dealing with a series of academic theses like Luther’s , one thus has to study both the theses themselves and ( if available ) the resolutiones or propositiones which followed . In Luther’s case , we have the resolutiones to most of his early disputation theses , including these . If one hopes to get the gist of the early Reformation by reading the 95 Theses , one must also digest Luther’s explanations – and indeed be aware of their sheer size : the two oldest surviving editions of the theses themselves are broadsides ; 6.6. Josef Benzing and Helmut Claus , Lutherbibliographie . Verzeichnis der gedruckten Schriften Martin Luthers bis zu dessen Tod , 1 , Baden-Baden 2 1989 ( Bibliotheca bibliographica Aureliana 10 ) , 16 , nos 87 – 88. The two known broadsides are from Nuremberg and Leipzig . It is an on-going debate whether there was an initial print from Wittenberg which was lost . It has been recently suggested that Luther was involved in the production of the Leipzig print ; see Thomas Kaufmann , Druckerpresse statt Hammer , in : Frankfurter Allgemeine Zeitung , 31 Oct. 2016 , 6. the corresponding Resolutiones disputationum de indulgentiarum virtute come to 120 pages in the smaller quarto format . 7.7. Cf. WA 1 , 523.

Despite their length , Luther must have handwritten – or had written – at least three manuscript copies of his Resolutiones . One version became the basis for the eventual print that was completed by August 1518. The other two reveal whom Luther intended to keep informed about the exchange of arguments : the first of these manuscripts was sent in February 1518 to Hieronymus Scultetus to satisfy the requirements of episcopal supervision and the second , three months later , to the Pope via Johann von Staupitz . 8.8. WA . Br 1 , 138 – 40 , 525 – 27. Luther’s letter to Scultetus survives and offers an interesting summary of previous events ; it is the earliest comprehensive account by Luther himself of what happened . According to this document , ‘ new and unheard-of doctrines ’ regarding apostolic indulgences had started to spread from the latest sales that had reached the region . 9.9. WA . Br 1 , 138. One has to bear in mind when reading these words that ‘ new ’ teaching was synonymous with heresy . The nature of apostolic doctrines is that they are old and go back to the origins of Christianity . Accordingly , this is Luther pointing out heretical elements in current church practices . Luther explains that his own involvement springs from a sense of spiritual and theological responsibility : simple and educated people alike have approached him for his own professional assessment . Luther claims to have initially responded in a reserved , non-committal way , but that this had backfired , since it increased and sharpened the criticism he faced . His solution was not to take sides , but to open up a debate , ‘ until the holy church ’ had taken a binding decision on the topic . 10.10. WA . Br 1 , 139. Hence ‘ I sent out the disputation , inviting and asking everyone publicly , and asking the most learned scholars I knew privately , so that they might at least reveal their opinion in writing ’ . 11.11. WA . Br 1 , 139 ( reading novi instead of the conjecture nosti ) . The reactions disappointed Luther . Scholars did not answer : on the contrary , the text was circulated more widely and was mistaken for ‘ assertions ’ instead of theses intended for a debate . 12.12. WA . Br 1 , 139. If one turns to the original invitation to the 95 Theses at the beginning of the translated text in this edition , it corresponds with the summary just given . It has to be stressed , however , how unusual this procedure was . Luther’s introduction does not fix a date for the disputation and it does not state who the protagonists would be . In Wittenberg there is only one other example of such an arrangement for a disputation . Six months earlier , in April 1517 , Luther’s theological colleague Andreas Bodenstein , named after his Franconian native town of Karlstadt , issued a series of 152 theses which documented his farewell to the scholastic teaching traditions in which he had himself excelled as Wittenberg’s most prolific and versatile exponent , and showcased his new affiliation with an Augustinian-based theology of grace . 13.13. Edited by Ulrich Bubenheimer and Martin Keßler , in : Thomas Kaufmann ( ed. ) , Kritische Gesamtausgabe der Schriften und Briefe Andreas Bodensteins von Karlstadt , 1 / 1 : 1507 – 1517 , Gütersloh 2017 ( Quellen und Forschungen zur Reformationsgeschichte 90 / 1 ) , 499 – 511. Karlstadt , too , had left the intended time and participants open . His correspondence reveals that he had hoped to attract the leading scholars in the territory to take part in a major disputation in Wittenberg . 14.14. Ulrich Bubenheimer and Martin Keßler , Einleitung , in : Kaufmann , Gesamtausgabe , 485 – 98 , here : 494 – 95. It has been suggested that Karlstadt might have been inspired in this format by Pico della Mirandola who had planned to debate 900 theses before a huge audience in 1487. 15.15. For the discovery and documentation of Karlstadt’s knowledge of the text , see the introduction and edition by Ulrich Bubenheimer , in : Kaufmann , Gesamtausgabe , 365 – 71. Neither Karlstadt’s nor Luther’s theses led to an actual disputation . Still , in Luther’s case it is clear that the intended audience would have been a locally or regionally restricted academic one . 16.16. Cf. WA . Br 1 , 113 – 14. In March 1518 Luther confirmed this to his former Wittenberg colleague from the Faculty of Law , Christoph Scheurl , who had returned to his hometown Nuremberg to take up a senior municipal post . 17.17. WA . Br 1 , 152 .

To some extent , Scheurl was responsible for the theses being more widely publicized and distributed , especially in the south of Germany . One of the two known broadsides , printed like a poster just on one side of folio-sized paper , is from Nuremberg and was forwarded by Scheurl to Johannes Eck , a rising theological star at the University of Ingolstadt . Scheurl has been described as an ‘ enthusiast of friendship ’ 18.18. Gustav Bauch , Christoph Scheurl in Wittenberg , in : Neue Mitteilungen aus dem Gebiete historisch-antiquarischer Forschungen 21 ( 1903 ) , 33 – 42 , here : 33. or the ‘ platform and networking service of German humanism ’ 19.19. Johann Peter Wurm , Johannes Eck und die Disputation von Leipzig 1519. Vorgeschichte und unmittelbare Folgen , in : Markus Hein and Armin Kohnle ( eds ) , Die Leipziger Disputation 1519. 1. Leipziger Arbeitsgespräch zur Reformation , Leipzig 2011 ( Herbergen der Christenheit , special vol. 18 ) , 95 – 106 , here : 96. . His goal was to instigate and encourage relationships between his own numerous friends . Attempts to recommend Eck and Luther to one another started off promisingly , but did not really develop . Scheurl had sent disputation theses from Eck to Wittenberg in April 1517 ; Luther did not reply directly , but asked Scheurl to forward his so-called Disputatio contra scholasticam theologiam to Eck in October 1517. 20.20. Peter Fabisch and Erwin Iserloh ( eds ) , Dokumente zur Causa Lutheri ( 1517 – 1521 ) , 1 : Das Gutachten des Prierias und weitere Schriften gegen Luthers Ablaßthesen ( 1517 – 1518 ) , Münster 1988 ( Corpus Catholicorum 41 ) , 376 – 77. By the end of the first week of 1518 , Scheurl had distributed the 95 Theses widely . He had sent them to Augsburg and Ingolstadt ; one of his friends had produced a German translation ; and Eck had been responsive enough to announce that he would walk ten miles in order to debate with Luther . 21.21. Fabisch / Iserloh , Dokumente , 377. For the political background to the German translation see Wilhelm Ernst Winterhager , Die Verkündigung des St. Petersablasses in Mittel und Nordeuropa 1515 – 1519 , in : Andreas Rehberg ( ed. ) , Ablasskampagnen des Spätmittelalters . Luthers Thesen von 1517 im Kontext , Berlin 2017 ( Bibliothek des Deutschen Historischen Instituts in Rom 132 ) , 565 – 610 , here : 594. Interestingly , what Eck did with the 95 Theses was no different from what Luther had done : he presented them to his local bishop and offered an annotated version . 22.22. Fabisch / Iserloh , Dokumente , 378 – 79. Winterhager , Verkündigung , 595 – 96 , reconstructs the personal and structural involvement of the bishop of Eichstätt in questioning the indulgence campaign . Eck’s remarks show that he , too , saw potential heresy , but this time on Luther’s side . On eleven consecutive theses he remarked that they were ‘ crude and tasteless , or rather they taste like Bohemia ’ . 23.23. Fabisch / Iserloh , Dokumente , 435. The ‘ Bohemian poison ’ , 24.24. Fabisch / Iserloh , Dokumente , 431. as he also calls it , was a reference to the last great heresy that had brought war to an entire nation : that of Jan Hus , the scholar from Prague who had taken up the theological promptings of the Oxford theologian John Wyclif . 25.25. On the various aspects of this topic see František Šmahel ( ed. ) , A companion to Jan Hus , Leiden [ etc. ] 2015 ( Brill’s companions to the Christian tradition , 54 ) . Specifically on Hus and indulgences , see Pavel Soukup , Jan Hus und der Prager Ablassstreit von 1412 , in : Rehberg , Ablasskampagnen , 523 – 64 , here : 485 – 500. Eck went on to become Luther’s and Karlstadt’s opponent in the Leipzig Debate in 1519 , the Reformation’s first actual disputation that reached a wide audience . 26.26. Hein / Kohnle , Disputation . Following the Leipzig Debate , Eck travelled to Rome and worked out the papal bull that threatened Luther with excommunication in 1520.

So far we have looked at the nature of academic disputations and found that , to some extent , Luther kept to the established procedure , but also opened it up . What might strike one as puzzling in all this is Luther’s incidental and yet central claim : that the church’s teaching on indulgence had not been finalized . Was this the case , and what are indulgences anyway ? Luther’s first thesis introduces the term by referring to Matthew 4 : 17 and Jesus’s call to ‘ Do penance ’ ( or ‘ Repent ’ ) , ‘ for the kingdom of heaven has come near . ’ He could just as well have quoted Matthew 3 : 2 , since Jesus himself is taking up the words of John the Baptist . Penance or penitence ( lat . poenitentia ) 27.27. See the note to thesis 1 of Luther’s 95 Theses in this edition , p. 33. initially described the one and only life-changing turning point in an individual’s development towards God . The Greek ‘ metanoia ’ ( μετάνοια ) can refer to this very process : a complete and utter change to a human’s inner disposition or direction . Penance and baptism almost coincided as the key moment of rearranging the relationship to God . Implicitly this involved the hope of living without deviating further from God . But this raised a fresh problem : What happened if followers relapsed ? From this question a shift in terminology transformed the fundamental dimension of distance from God into a selection of outrageous acts . In particular , three main sins developed from the Ten Commandments : denying or renouncing God ( ‘ apostasy ’ ) , adultery , and murder . Various options were considered about how to handle these and other violations . A radical view was expressed in Hebrews 6 : 4 – 8 : Whoever sins after baptism is to be excluded from the church for good . It is questionable whether this position was ever actually applied . Another position was taken in a visionary text , the Shepherd of Hermas , written around 100 A.D. After baptism , so the suggestion goes , the sinner could be reintegrated into the congregation , but only once , ‘ since for the servants of God there is just one penance ’ . 28.28. Die Apostolischen Väter . Griechisch-deutsche Parallelausgabe auf der Grundlage der Ausgaben von Franz Xaver Funk , Karl Bihlmeyer und Molly Whittaker mit Übersetzungen von M. Dibelius und D . -A . Koch neu übersetzt und herausgegeben von Andreas Lindemann und Henning Paulsen , Tübingen 1992 , 380 – 81 ( mandatum IV , 8 ) . Although Hermas dealt with adultery , it was the offence of apostasy that became a mass phenomenon during the centuries to come . In the wake of various conflicts and schisms , practical solutions evolved . 29.29. Cf. Wolfram Kinzig and Martin Wallraff , Das Christentum des 3. Jahrhunderts zwischen Anspruch und Wirklichkeit , in : Dieter Zeller ( ed. ) , Christentum I. Von den Anfängen bis zur Konstantinischen Wende , Stuttgart 2002 ( Religionen der Menschheit 28 ) , 331 – 88. These included bishop Basilius of Caesarea recording a number of authoritative canones and suggesting a two-step procedure : public confession by the sinner before the congregation , followed by the church’s proposal of special works of penance . Three acts were recommended and performed in particular : prayer , fasting , and almsgiving . 30.30. On the biblical background , see the note to §3 of the Sermon on Indulgences and Grace in this edition , p. 7.

The transitional period between Late Antiquity and the early Middle Ages witnessed two tendencies . 31.31. Cf. Arnold Angenendt , Grundformen der Frömmigkeit im Mittelalter , München 2 2004 ( Enzyklopädie deutscher Geschichte 68 ) , 43. Under one of these tendencies , Augustine highlighted the universal dimensions of sin , with the result that the more extensively sin was understood to refer to all sorts of human attitudes and actions , the more inclusively penance had to be defined . Accordingly , under the second of these tendencies , the act of penance turned into a highly specialised institution during the Middle Ages . Owing to the huge quantity and wide variety of possible offences , the previously public confession turned into a private procedure between culprit and confessor . Highly influential in the British Isles and on the continent were the monks from Ireland and Scotland who drew up detailed , comprehensive catalogues about the appropriate relationship between deeds and penalties . 32.32. Arnold Angenendt , Das Frühmittelalter . Die abendländische Christenheit von 400 bis 900 , Stuttgart [ etc. ] 2 1995 , 210. The increase in the number of penalties imposed gave rise to two trends . Firstly , more physically demanding , intensive forms of prayer and fasting started to develop , replacing the more time-consuming activities carried out previously . 33.33. Angenendt , Frühmittelalter , 211. Arnold Angenendt , Geschichte der Religiosität im Mittelalter , Darmstadt 1997 , 637. From this the second trend evolved , which was that not only the act of penance , but also the performer of the act , could be substituted ; thus , instead of praying , one could consider giving alms to a monk to do so . 34.34. Angenendt , Religiosität , 639. The concept of personal commutation 35.35. Angenendt , Frühmittelalter , 211. Angenendt , Religiosität , 636 – 39. was connected with endowments . By funding or supporting monasteries , landlords could expect to profit personally from the monks ’ prayers . From these , a hierarchy of works developed : collective efforts were better than individual works ; the merits of saints surpassed those of the living ; and the benefits of Christ trumped all of these as well as the merits of the Apostles . 36.36. Angenendt , Religiosität , 653 – 54. The theory of thesaurus ecclesiae , the Treasury of Merits that transcended time and space , followed from this and was elaborated academically in the 13th century . 37.37. Gustav Adolf Benrath , Ablaß , in : Gerhard Krause and Müller Müller ( eds ) , Theologische Realenzyklopädie 1 , Berlin [ etc. ] 1977 , 347 – 64 , here : 349. Around this time , the term indulgentia began to replace older concepts of personal exchange and participation in remission . 38.38. Benrath , Ablaß , 347. A related question that had troubled Christians since their early history was God’s final judgement : When was this due – after an individual’s death or at the end of time ? Various concepts developed and even merged . 39.39. Instructive on the topic is Peter Jezler , Himmel , Hölle , Fegefeuer . Das Jenseits im Mittelalter . Eine Ausstellung des Schweizerischen Landesmuseum in Zusammenarbeit mit dem Schnütgen-Museum und der Mittelalterabteilung des Wallraf-Richartz-Museums der Stadt Köln , München 2 1994. For some , such as saints , John 5 : 24 – 29 might apply and offer direct passage to eternal life . Most , however , had to await a final judgement as described in Matthew 25 : 31 – 46 , either individually ( ‘ particular judgement ’ ) or collectively ( ‘ universal judgement ’ ) . The potential punishments took time ; thus , some souls had to pass through a purifying period before being granted eternal life in heaven . This idea of an intermediate stage has a long tradition 40.40. The classic work is Jacques le Goff , The Birth of Purgatory , London 1984. A solid summary is given by Angenendt , Religiosität , 706 – 08. For illustrative references , including Bede , see Meinolf Schumacher , Sündenschmutz und Herzensreinheit . Studien zur Metaphorik der Sünde in lateinischer und deutscher Literatur des Mittelalters , München 1996 ( Münstersche Mittelalter-Schriften 73 ) , 469. and was identified with a purgatory ( lat . purgatorium ) which was more closely defined , theologically and dogmatically , from the 13th century onwards . In precise terms , purgatory offered satisfaction to sinners who had taken the first steps towards penance but who had not managed to perform the acts imposed during their lifetime . 41.41. See the note to thesis 15 of Luther’s 95 Theses in this edition , p. 36. For Martin V’s bull Inter cunctas from 1418 implying this , see Heinrich Denzinger , Kompendium der Glaubensbekenntnisse und kirchlichen Lehrentscheidungen . Verbessert , erweitert , ins Deutsche übertragen und unter Mitarbeit von Helmut Hoping ed. by Peter Hünermann , Freiburg [ etc. ] 43 2010 , 416 , no . 1266. For guidance on further documents relevant to this topic see Denzinger / Hünermann , Kompendium 1692 , K10b . This is where indulgence , and indulgences , come in . In 1300 , Boniface VIII was the first pope to announce a ‘ holy year ’ in which complete remission of sins was offered to visitors to Roman churches who had truly repented and confessed . 42.42. Denzinger / Hünermann , Kompendium , 358 , no . 868. Acts of penance were accordingly still required and not completely eliminated . Four decades later , Pope Clemens VI’s bull Unigenitus Dei filius linked the Church’s administration of its treasury , the thesaurus ecclesiae mentioned above , to the granting of indulgence ( i.e. dispensation ) for the remission of acts of penance according to specific temporal , local , and personal conditions . 43.43. Corpus iuris canonici . Editio Lipsiensis secunda post Aemilii Ludovici Richteri , curas ad librorum manu scriptorum et editionis Romanae fidem recognovit et adnotatione critica instruxit Aemilius Friedberg , 2 : Decretalium collectione , Leipzig 1879 [ reprint Graz 1959 ] , 1304 – 06. Denzinger / Hünermann , Kompendium , 384 , no . 1025 – 27. The ‘ holy year ’ of 1300 illustrates the basic pattern of such conditions and became a model for further holy years , events , and places that involved activities leading to the benefit of indulgence . Starting in Rome , such offers were at first geographically restricted and then became available all over Europe , taking a wide variety of cultural forms . The requirement to be physically present in Rome to be granted indulgence was relaxed and other means of involving relevant places or people were developed . Thus , ‘ ad instar’-indulgences offered measures of indulgence equivalent to what had been defined elsewhere . Connections between , for example , an Italian church ( and its offers of indulgence ) and venues in Germany were legally fixed – and , as it turned out , later revoked – in papal documents . Relics were another means of participating in the thesaurus ecclesiae , and thus , in indulgence , in that they granted personal or physical contact to valued figures of the Christian past . 44.44. Hartmut Kühne , Ostensio reliquiarum . Untersuchungen über Entstehung , Ausbreitung , Gestalt und Funktion der Heiltumsanweisungen im römisch-deutschen Regnum , Berlin 2000 ( Arbeiten zur Kirchengeschichte 75 ) . For a brief account with valuable updates : Hartmut Kühne , Ablassvermittlung und Ablassmedien um 1500. Beobachtungen zu Texten , Bildern und Ritualen um 1500 in Mitteldeutschland , in : Rehberg , Ablasskampagnen , 427 – 57. Pilgrimages provided another pathway to indulgence , if they involved visiting places with valued relics on special dates for particular benefits . By the end of the 15th century , indulgences had turned from an exclusive to an extensive good . As in 1300 in Rome , it started off as a locally and temporally restricted offering , and within a century had met with huge demand resulting occasionally in inflationary supply . The national and international dimensions of this have recently been carefully documented and critically reviewed , both for England and the rest of Europe . 45.45. R.N. Swanson ( ed. ) , Promissory Notes on the Treasury of Merits . Indulgences in Late Medieval Europe , Leiden 2006 ( Brill’s Companions to the Christian Tradition 5 ) . R.N. Swanson , Indulgences in Late Medieval England . Passport to paradise ? , Cambridge [ etc. ] 2007. Abigail Firey ( ed. ) , A New History of Penance , Leiden [ etc. ] 2008 ( Brill’s Companions to the Christian Tradition 14 ) .

Classic Protestant perspectives have tended significantly to devalue and degrade the medieval indulgence trade . Nevertheless , even in older scholarship there is a tradition of reassessing the status of this practice . To some extent one could interpret the magnum opus of Nikolaus Paulus , one of Max Weber’s earliest readers , as a counter-part to Weber’s own classic study on The Protestant Ethic and the Spirit of Capitalism . Paulus’s Geschichte des Ablasses am Ausgang des Mittelalters sets about interpreting ‘ indulgences as a social factor in the Middle Ages ’ , as an English translation of one of its central passages puts it . 46.46. Indulgences as a Social Factor in the Middle Ages . By Nikolaus Paulus . Translated by J. Elliot Ross. With a foreword by Eugene C. Barker , New York 1922. The latest edition of the original work has appeared with some bibliographical additions : Nikolaus Paulus , Geschichte des Ablasses am Ausgang des Mittelalters , 3 vols , Darmstadt 2 2000. Indulgence campaigns , according to Paulus , did not just accumulate and alienate capital by exporting it from the territories , but the resources raised were substantially reinvested in local and regional infrastructure , e.g. by promoting and financing the building of new roads that were necessary to access places of worship and pilgrimage . In more recent Protestant scholarship , a new awareness has developed about the spiritual dimensions of indulgence practices . Bernd Moeller thought that he detected a ‘ trace of the Gospel ’ in them , 47.47. Bernd Moeller , Die letzten Ablaßkampagnen . Luthers Widerspruch gegen den Ablaß in seinem geschichtlichen Zusammenhang , in : Bernd Moeller , Die Reformation und das Mittelalter , Kirchenhistorische Aufsätze , ed. by Johannes Schilling , Göttingen 1991 , 53 – 72 , here : 54. before Berndt Hamm noted ‘ amazing congruences ’ between the quest for certainty in salvation during the Middle Ages and in the Reformation . According to Hamm , conflicting contemporary responses were close yet different : the acquisition of indulgence involved a ‘ minimum ’ of a person’s own efforts – receiving the gift of the Gospel none . Hamm calls this move from gradual human involvement to an exclusively divine act a ‘ quantum leap ’ . 48.48. Berndt Hamm , Ablass und Reformation . Erstaunliche Kongruenzen , Tübingen 2016 , 159 , 168 , 244. Social and economic studies of German indulgence campaigns are very valuable . Wilhelm Ernst Winterhager 49.49. Wilhelm Ernst Winterhager , Ablaßkritik als Indikator historischen Wandels vor 1517 : Ein Beitrag zu Voraussetzungen und Einordnungen der Reformation , in : Archiv für Reformationsgeschichte 90 ( 1999 ) , 6 – 71. challenged the established assumption that the indulgences which were offered enjoyed widespread demand . By comparing the geographical and financial aspects of indulgence sales in the Holy Roman Empire of the German Nation around 1500 , he noted two significant developments . 50.50. Winterhager , Ablaßkritik , 22 – 34. In the years before Luther issued the 95 Theses , organized indulgence sales had narrowed from Empire-wide to territorial campaigns . In big cities such as Nuremberg and Frankfurt am Main , revenues raised by indulgence commissioners fell dramatically in some areas and remained substantial in others . This gave rise to the second development : the territorial campaigns from 1513 onwards shifted their focus from cities to remoter and more rural areas . The infamous campaign organized by Albrecht of Mainz falls into this category . 51.51. Winterhager , Verkündigung , 585 – 86. The sale to fund the building of St Peter’s Basilica in Rome initially ran from 1515 to 1518 under the direction of the papal legate Arcimboldi in the church provinces of Cologne , Trier , and Bremen and the dioceses of Meißen and Kammin . 52.52. For a summary see Winterhager , Ablaßkritik , 23 , in more detail Winterhager , Verkündigung , 569 – 73. When Albrecht of Mainz negotiated in 1514 the option of becoming archbishop of Magdeburg , his representatives had strong reservations after the papal side suggested that Albrecht should promote the indulgence campaign as a means of financing the deal . 53.53. Winterhager , Ablaßkritik , 40. See also Winterhager , Verkündigung , 566 – 67. Albrecht’s associates had been fully aware of the ‘ aversion ’ that this type of campaign was liable to provoke . 54.54. Winterhager , Ablaßkritik , 40. Others , including Albrecht of Brandenburg-Ansbach , turned down such offers , raising similar concerns . 55.55. Winterhager , Ablaßkritik , 40 – 41 ; Winterhager , Verkündigung , 575 – 76. The indulgence trade organized by Albrecht from 1516 to 1518 was confined to his territories of Mainz , Magdeburg , and Brandenburg . 56.56. Winterhager , Ablaßkritik , 23.

All this has to be borne in mind when we come back to the letter which Luther wrote to Albrecht of Mainz enclosing the 95 Theses . It refers to practices in neighbouring regions in which a limited , but highly effective , campaign was being conducted . These areas added up to more than half of the German territories within the Holy Roman Empire . Most of the other parts were handled by Arcimboldi , who was also involved in Sweden and Finland . 57.57. Winterhager , Verkündigung , 567. Maps of the campaign offer an excellent overview of the territories and countries involved : Hartmut Kühne , Enno Bünz , and Peter Wiegand ( eds ) , Johann Tetzel und der Ablass . Begleitband zur Ausstellung ‘ Tetzel – Ablass – Fegefeuer ’ in Mönchenkloster und Nikolaikirche Jüterbog vom 8. September bis 26. November 2017 , Berlin 2017 , 293 – 98. After Emperor Maximilian had legalized the sale of indulgences in the Holy Roman Empire in 1515 , 58.58. Winterhager , Verkündigung , 568. many German territories and cities remained sceptical about the new campaign . 59.59. Winterhager , Verkündigung , 582 – 98. Territorial , regional , or local resistance was feasible , but it was subject to Roman and canon law as well as to the pragmatic consideration of how far Albrecht of Mainz was prepared to go in his legal response given the risk of further opposition from other territorial rulers . 60.60. Winterhager , Verkündigung , 589. The Albertine Duke of Saxony , George , actively prevented the sale in his territory , since he objected to the loss of revenue that would have resulted in his area . 61.61. Winterhager , Verkündigung , 589. Like all other sovereigns – except Albrecht of Mainz , the Emperor who had received a substantial sum for his permission , 62.62. See note 58 and Fabisch / Iserloh , Dokumente , 210. and the Pope – he did not profit from the proceeds . In March 1517 , Luther’s sovereign , the Elector Frederick the Wise , and his brother Johann responded similarly in their territories , 63.63. Peter Wiegand , in : Netzwerke eines ‘ berühmten Practicus ’ ? Was Tetzel zum erfolgreichen Ablasskommissar machte , in : Kühne / Bünz / Wiegand , Tetzel , 124 – 60 , here : 149. although no documents have been identified to support the notion that they had financial motives for doing so . 64.64. Peter Wiegand , Marinus de Fregeno – Raimund Peraudi – Johann Tetzel . Beobachtungen zur vorreformatorischen Ablasspolitik der Wettiner , in : Rehberg , Ablasskampagnen , 305 – 33 , here : 325. In any case , the vast collection of relics housed in the Castle Chapel of Wittenberg , the city’s main church institution , which had been granted extensive privileges , offered an impressive number of indulgences . Still , the difference between plenary indulgences – the remission of all sins – and partial indulgences , as abundant as they may have been , remained . Only a year before denying the latest campaign access to his territories , Frederick the Wise had requested permission from the Pope to increase the number of indulgence associated with his relic collection in Wittenberg . 65.65. Paulus , Geschichte 3 , 245.

In terms of indulgences , the campaign to support the building of St Peter’s had more to offer . The campaign was announced in Leo X’s bull Sacrosanctis of 31 March 1515 , 66.66. Fabisch / Iserloh , Dokumente , 212 – 24. and promoted plenary indulgences to a wide range of potential buyers . The bull describes in great detail the offences to be dealt with and the applicable financial contributions . The latter included temporarily redirecting to the campaign existing endowments to churches or brotherhoods . Acquirers of indulgences could select the priest to whom they made confession , and special documents instructed confessors accordingly . The offer of complete remission of all sins applied to laypeople and clerics alike , dead or alive . The thesaurus ecclesiae 67.67. Fabisch / Iserloh , Dokumente , 222 – 23. referred to in the bull allowed apostolic successors , i.e. the pope and his official representatives , to administer and distribute the benefits it contained .

The bull itself did not trigger the campaign immediately since the subsequent negotiations took time . In 1516 Albrecht of Mainz was legally guaranteed half of the profits , but the operations in his territories could not start until 1517. 68.68. Fabisch / Iserloh , Dokumente , 211. By then , the sale organized by Arcimboldi was up and running , and it is likely that Luther had already come across preachers from this leg of the campaign in 1516. 69.69. Summing up Wolfgang Breul’s argument : Volker Leppin , Das ganze Leben Buße . Der Protest gegen den Ablass im Rahmen von Luthers frühen Bußtheologie , in : Rehberg , Ablasskampagnen , 523 – 64 , here : 547 , note 116. Apart from personal interactions , printing played an important role in publicizing the particular terms of the indulgence , as recent discoveries have shown . Summaries of the papal bull appeared in broadsides , fragments of which have been identified in both Latin and German . 70.70. Ulrich Bubenheimer , Druckerzeugnisse aus der Leipziger Offizin Melchior Lotters d . Ä . für den von Albrecht von Brandenburg vertriebenen Petersablass und deren Funktion , in : Kühne / Bünz / Wiegand , Tetzel , 267 – 85. The complete text of the German summary can be reconstructed from a quarto edition that had been considered missing since 1899 , 71.71. On the print cf. Bubenheimer , Petersablass , 276 : ‘ Hier wird ein Druck vorgestellt , der gegenwärtig verschollen ist ’ with 277 , note 51. but which was rediscovered in 2017 . 72.72. Dis ist ain kurtzer begriff oder Summa der macht vnnd artickel / des aller volkommlichsten / vnnd aller hailigsten Ablaß etc. ( BSB München , sig . Rar . 1873#Beibd . 2 ) , digitally available at http : / / daten . digitale-sammlungen.de / ~db / 0011 / bsb00110038 / images / . To our knowledge , this summary of the bull represents the most popular printed text containing information on the terms and conditions of the offering . The German version entirely matches the Latin fragments ; it can be concluded that one text was distributed in two languages and printed in at least two different formats . The title page does not survive , 73.73. For a suggestion on this see Bubenheimer , Petersablass , 277. but the header on the first page announces a summary ( Summa ) of the bull that was to offer ‘ the most perfect ’ indulgence of ‘ pein ’ and ‘ schuldt ’ , 74.74. Summa , A2r . the German equivalents of poena and culpa . ‘ Pein ’ ( translated in this edition as ‘ punishment ’ ) 75.75. See the first note to thesis 4 in the 95 Theses , p. 34. refers to works of satisfaction imposed in life or the temporal , purifying punishments after death . ‘ Schuldt ’ ( translated as ‘ guilt ’ ) concerns the principal dimension of human responsibility and divine acceptance or rejection . Even though the institution of penance dealt with forgiveness ( or ‘ remission ’ ) of ‘ guilt ’ , it was still possible for the required works of satisfaction – and the related ‘ punishment ’ – to remain . The bull and its publicity material might appear imprecise , but they do in fact use an established term for plenary indulgences . 76.76. With reference to this text and traditions dating back to the 13th century , see Nikolaus Paulus , Johann Tetzel der Ablaßprediger , Mainz 1899 , 97 – 98. The bull itself involves another pair of terms which have found their way into the vernacular summary by referring to indulgences and other benefits : ‘ indulgentias et alias gratias ’ . 77.77. Fabisch / Iserloh , Dokumente , 215. The German summary uses the combination of ‘ ablaß ’ and ‘ gnad ’ frequently as a reference to the current papal offering . 78.78. Cf. Summa , Avr , , A4v . It is not just the sermons of indulgence preachers , but also this very document which spread the word about the indulgence campaign among large numbers of people .

As a preacher , Luther began to deal with the topic of indulgences and recent developments related to them either in late 1516 or in early 1517. 79.79. For a summary of earlier suggestions cf. WA 1 , 94 , note 1. A more recent appraisal has been offered by Leppin , Buße , 546 – 47 , note 116. The first relevant text survives within a sequence of sermons delivered from 1514 to 1517 and is recorded in Latin . 80.80. WA 1 , 20 – 141 , here : 94 – 99 ; for another version see WA 4 , 670 – 74. For useful summaries and references : Erwin Iserloh , Luther zwischen Reform und Reformation . Der Thesenanschlag fand nicht statt , Münster 3 1966 ( Katholisches Leben und Kämpfen im Zeitalter der Glaubensspaltung 23 / 24 ) , 31 – 35. The language has been interpreted as indicating that the sermon was intended for publication ; 81.81. Cf. Karl Knaake in WA 1 , 19. it has been argued , too , that the text might not be from the municipal church in which Luther preached , but from the chapel of the Augustinian monastery . 82.82. Theodor Brieger , Kritische Erörterung zur neuen Luther-Ausgabe , in : Zeitschrift für Kirchengeschichte 11 ( 1890 ) , 100 – 54 , here : 122. In any case , the sermon proposes that man is saved by divine grace alone and it firmly opposes indulgence teaching that undermines this fundamental understanding . 83.83. WA 1 , 98 – 99. While the pope’s motives might be ‘ right and true ’ , Luther identifies the culprits as the preachers who act as ‘ seducers ’ and ‘ storytellers ’ . 84.84. WA 1 , 98. In general , Luther summarizes penance as theologically consisting of three parts : a person’s heartfelt regret ( lat . contritio cordis ) , the act of confession ( confessio oris ) , and satisfaction ( traditionally based on works : satisfactio operis ) . 85.85. Cf. the respective allusions in WA 1 , 98 – 99. See also the note to thesis 12 of the 95 Theses , p. 35. Even in this early sermon , Luther emphasised that all of these aspects are vital , but must be understood and applied internally , spiritually . 86.86. Esp. WA 1 , 99.

In short , this sermon already provides the backbone of the 95 Theses and the Sermon on Indulgences and Grace . Both texts start off with the established theological understanding of penance . 87.87. For a useful brief summary of the contemporary diversity of positions and arguments – including those of Thomas Aquinas and Petrus Lombardus – see Leppin , Buße , 526 – 34. A good translation of Lombard’s relevant passages is available : Peter Lombard , The Sentences . Book 4 : On the Doctrine of Signs . Translated by Giulio Silano , Toronto 2010 ( Medieval Sources in Translation 48 ) , 69 – 135. For the tripartite structure referred to by Luther see Lombard , Sentences , 88. The Sermon names the three related components in its first point , while readers of the disputation have to combine theses 2 and 12 ( or later 30 , 35 , 39 – 40 , and 87 ) in order to identify and connect the relevant terms on the basis of their previous knowledge . Both texts proceed to deal with further scholastic statements on theoretical or practical aspects . More or less implicitly , Luther relates these to their appropriate authorities : the bible , early church teachings , canon law and scholastic school traditions , reason , and every so often concludes that they derive from mere imagination . It is clear that Luther advocates a revision of later developments relating to indulgences on the basis of biblical authority .

Ill. 3 : The 95 Theses in pamphlet format , [ Basel : Adam Petri ] 1517 , A1v UB Basel KiAr J VI 30 : 1 ( http : / / doi . org / 10.3931 / e-rara-273 )

The 95 Theses start off with a biblical understanding of penance , while the Sermon on Indulgences and Grace , as a popular piece of writing , opens with a definition of terms . One of the great advantages of the Sermon over the 95 Theses is its clear structure . Its title presents two terms , which correspond to two sections into which the twenty points are organized ( see the black border in the table below ) . The word ‘ grace ’ appears once only in the text ( in point 13 ) , but it is highlighted by the title and is present in the line of argument . The combination of terms provides a striking response to the vernacular summary of the papal bull . 88.88. See note 78. At the same time , the formal structure of the Sermon corresponds to the Latin and German Summa in its length and division into around twenty points . Since the German Summa must , as things stand , be considered the most popular printed text in the campaign , the even more popular Sermon might be considered an answer to the promotional publicity of the bull’s summaries . 89.89. Ulrich Bubenheimer , Reliquienfest und Ablass in Halle . Albrecht von Brandenburgs Werbemedien und die Gegenschriften Karlstadts und Luthers , in : Stefan Oehmig ( ed. ) , Buchdruck und Buchkultur im Wittenberg der Reformationszeit , Leipzig 2015 ( Schriften der Stiftung Luthergedenkstätten 21 ) , 71 – 100 , reconstructed in great detail Luther’s and Karlstadt’s reactions to Albrecht of Mainz’s offers of indulgences in Halle between 1520 and 1522. He classifies the Archbishop’s prior publications as ‘ promotional advertisements ’ ( ‘ Werbung ’ ) , 81 – 82 , 90. Bubenheimer’s analysis reinforces the interpretation given above . While Luther’s Sermon adheres in important aspects of its format and content to the most widely distributed printed tracts of the campaign , his own classification of it as a Sermon gives it a spiritual and pastoral framework .

A summary of its contents ( below ) illustrates its structure and highlights how Luther introduces particular elements of scholastic teaching traditions , questions their authority , and compares them with what he understands the corresponding biblical foundation to be . The first column lists the paragraph of the Sermon followed by the topics , the theological doctrines in the scholastic tradition , the authorities according to Luther , and finally Luther’s own position . The shaded area accentuates the Sermon ’s positive message and Luther’s advice .

| § | Topics | Scholastic tradition | Authorities | Luther’s position |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. | Penitence | Comprises ( 1 ) Contrition ( 2 ) Confession ( 3 ) Satisfaction | Unscriptural , unpatristic | |

| 2. | Indulgence | Requires 1 and 2 , refers to 3 | ||

| 3. | Satisfaction | Combines acts of a ) Prayer b ) Fasting c ) Almsgiving | ||

| 4. | Indulgence and satisfaction | Indulgences partially reduce the works imposed | ||

| 5. – 6. | Indulgence and ‘ punishment ’ | Controversial whether indulgences reduce divine ‘ punishment ’ | Unscriptural ‘ opinion ’ ( 6 ) | Biblical : contrition and works come from genuine motivation ( 6 ) |

| 7. – 8. | Biblical : divinely imposed ‘ punishment ’ leads to contrition ( 7 ) and is only partially understood by man ( 8 ) | |||

| 9. | Specification of divine punishments | Fictional ‘ prattle ’ | Divinely imposed ‘ punishment ’ is beneficial for man | |

| 10. | The total amount of ( temporal ) punishment might exceed an individual’s lifetime | ‘ empty words ’ and ‘ fabrication ’ | Biblical : God and the ‘ holy church ’ are moderate | |

| 11. | Canon law once related mortal sins to seven years of penance | Christians have to be moderate | ||

| 12. | Sins without satisfaction during one’s lifetime lead to purgatory ( or demand indulgence ) | ‘ without foundation and proof ’ | ||

| 13. | Grace | Satisfaction is necessary for the forgiveness of sins | ‘ error ’ | God’s forgiveness is free and expects only personal progress |

| 14. – 16. | Good works | Indulgences encourage human idleness ( 14 ) . Good works have to be done ‘ for God’s sake ’ ( 15 ) ; they should first help the needy nearby , then the local church , and only as a last resort the church in Rome or elsewhere | ||

| 17. – 20. | Summary | Indulgences rescue souls from purgatory ( 18 ) | ‘ impossible to prove ’ , ‘ opinions ’ , undecided by the church ( 18 ) | Suggested strategies include : don’t purchase indulgences ( 16 ) ; don’t hinder indulgence sales ( 17 ) ; encourage personal ‘ punishment ’ , charitable deeds , and prayers for others ( 18 ) . This advice is biblical ( 19 ) , steeped in Christian tradition , and not heretical ( 20 ) . |